Canadian Biker (Online) - October 1999

email edit@canadianbiker.com

Official web page at

http://www.canadianbiker.com/

Toll Free: 1-800-667-5667

This article reprinted with permission from Canadian Biker Magazine.Copyright © -1995 to 1999 Canadian Biker Magazine

Unauthorized reproduction or duplication prohibited.

Triumph Sprint

Side by Side...

By Robert Smith

Darren Kelly Photos

Old Sprint? New

Sprint? Which Sprint? Robert Smith says the old Sprint has a "fundamental

rightness," while the '99 ST is a product of Triumph's new-found ability

to play in the big boys' sandbox. Which bike to pick on a limited budget?

Decisions, decisions...

Over the brooding,

dark-forested Monashees of British Columbia hung a mottled overcast the colour

of mushroom soup. As I stood waiting on the gravel shoulder by Hwy Six, a misty

drizzle spotted the Nikon's zoom lens. No wind, no cars - just the occasional

squawk from foraging crows and the rush of water falling somewhere behind the

occluding trees.

Over the brooding,

dark-forested Monashees of British Columbia hung a mottled overcast the colour

of mushroom soup. As I stood waiting on the gravel shoulder by Hwy Six, a misty

drizzle spotted the Nikon's zoom lens. No wind, no cars - just the occasional

squawk from foraging crows and the rush of water falling somewhere behind the

occluding trees.

Going east from Lumby, I'd pulled a distance ahead of the group to take some motion shots. It was day two of Rocky Mountain Motorcycle Holidays' "Western Canada in a Week," - a chance for an extended ride on Triumph's new flagship bike, the '99 Sprint ST.

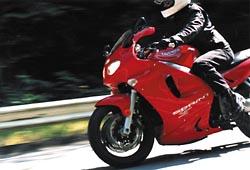

Across the road, the Sprint ST was a splash of crimson against the ashen rockface. I waited 10 - now 15 - now 20 minutes, checking and re-checking exposure settings. Was the ST really that fast? Finally, a green Trophy crested the rise and swooped past as I snapped away. Black and green Tigers, a black ST and a Speed Triple followed, trailed by RMMH's blue GMC dually. Photo op over, I packed the camera away and remounted the ST. Wouldn't take long to catch up...

Yes, the ST is that fast. Even on Hwy Six's damp, frost-heaved tarmac, it scurried round decreasing-radius turns and scampered over each successive rise toward the high pass. The torque-tuned engine hauled strongly from below 2,000 rpm, easing the need to stir the cogs; but snicking down and winding it on, the thing flew. The more aggressively I blasted from bend to bend, the better it seemed to bite in the turns. Brakes were rarely troubled, the overrunning engine dumping speed like a big twin. The odd dawdling camper was blown by on a whim. I hadn't expected to enjoy this as much. The bike's compact layout - short reach, high footpegs, swept back bars - didn't suit my long limbs. Grubbing along in traffic on Hwy 99 the day before, it handled like a bus. The controls felt heavy and awkward, weight and low-speed vibration caused my wrists to ache and my fingers to tingle.

But while pressing on, I realized what was wrong. Sitting back on the seat with my arms straight, the ST needed to be convinced through every bend. But with a subtle shift of weight, a straighter back, more relaxed arms, and - most importantly - a lot more speed, the ride was transformed. The Sprint and I melded: the steering lightened, my hands floated over the controls. Suddenly it just felt right.

I was reminded of

how ungainly aircraft are when landing, how they buck and sway, shudder and

roll. The Triumph Sprint ST needs to fly too. At speed it soars like a

sparrowhawk. A cunningly concealed duct in the fairing directs air under the

windshield, reducing buffeting while providing a gentle uplift for the rider.

Above 80 kmh, this synergy kicks in. The engine smooths out, the ducted air

lifts body weight off the arms, and the whole produces a sensation of floating.

Between 80 and about 180kmh, all is smoothness and light - though the

windshield does start to waggle its ears above 170... How then does this new

Sprint compare with its carburetted, steel framed forerunner? First a little

history. The Sprint was introduced into the 1993 Triumph range to answer demand

for a half-faired compromise between the naked Trident and the touring Trophy.

Like both of these bikes, it was based around Triumph's original concept of a

steel-tube spine frame (though it looks more like a bent drainpipe than a

backbone...) and the ubiquitous

97hp, 885cc, three cylinder, 12-valve

engine. Although a hit in Europe (and Triumph's best selling model for a

while), the Sprint failed to set North America on fire. In a world of cruisers

and crotch rockets, where does a semi-naked, semi-sport, semi-tourer fit? The

answer - my garage.

97hp, 885cc, three cylinder, 12-valve

engine. Although a hit in Europe (and Triumph's best selling model for a

while), the Sprint failed to set North America on fire. In a world of cruisers

and crotch rockets, where does a semi-naked, semi-sport, semi-tourer fit? The

answer - my garage.

I'd always fancied a Tiger, though. Its rugged appearance and go-anywhere getup looked the business. I even kidded myself I might take it off road until a test spin convinced me this was not A Good Idea. A porky 500lbs, most of it centred well above the seat, doesn't do it on the dirt. Then I spotted a leftover '96 Sprint in Port Coquitlam's International Motorcycles, marked down to a sum that would cause slightly less apoplexy in the Smith household. Tried it, liked it, got the T-shirt. I'm now convinced the old Sprint was one of Triumph Canada's best kept secrets. Same engine as the old Speed Triple, same running gear (mostly) as the Daytona. And a lower price than either.

In '98, the Sprint went schizophrenic, begetting two models - the Executive, with matching hard luggage, and the Sport, with three-into-one high pipe and lower bars. In '99, Triumph tossed the old design and produced a new peripheral alloy beam frame cradling a tuned-for-torque 955cc triple with Sagem fuel injection and the Daytona's single-side swingarm - all clad in a VFR-lookalike full fairing. A half-faired Sprint SR will arrive later this year with an even sportier outlook and no provision for luggage. The design philosophies that generated these machines are totally at odds. The earlier Triumphs were built on the basis of minimizing the then-small company's financial exposure. By using welded steel frames, modular engines and fabricating much else, major casting tool costs were avoided - a prime consideration for a startup that could have gone belly up.

As sales revenue

built and confidence grew, designers coul d turn their attention to reducing production costs, saving weight,

and updating technology. For example, the welded alloy swingarm common to all

early Triumphs (and still in use on the Trophy), though strong is heavy. It's

fabricated from rectangular-section alloy tube, taking considerable CNC time.

The new single-sided pressure die-casting for the Daytona, ST and Speed Triple

is no more than half the weight, and arrives in the factory needing little

preparation before assembly. These principles - more investment to produce

lighter, less machine-intensive components - are widely used in the ST,

starting with the cast alloy beam frame.

d turn their attention to reducing production costs, saving weight,

and updating technology. For example, the welded alloy swingarm common to all

early Triumphs (and still in use on the Trophy), though strong is heavy. It's

fabricated from rectangular-section alloy tube, taking considerable CNC time.

The new single-sided pressure die-casting for the Daytona, ST and Speed Triple

is no more than half the weight, and arrives in the factory needing little

preparation before assembly. These principles - more investment to produce

lighter, less machine-intensive components - are widely used in the ST,

starting with the cast alloy beam frame.

So is the new Sprint ST a sportbike or a tourer? With the fragmentation of the bike market into ever smaller niches, the ST seems to slot into the "Sport Tourer" category - but that depends on your definition of touring. The optional matching hardbags will take a toothbrush and a change of underwear, but loading on a tent would be a challenge. Don't even think about a trailer - this is a motel-to-motel tourer with supersports speed - not a Winnebikeo for the footboard and headset brigade.

I first tried the ST at Richmond Motorsports test-ride day. That bike was fitted with Triumph's carbon-fibre race can and remapped programming. Winding the grip in first produced a bellow worthy of Ben Heppner belting out Wagner's Siegfried, while the rear wheel tried to pass under the front. At 3,000 rpm the can resonated as sonorously as that same legendary hunter's horn. Next, I spent most of a week riding an ST with Mike Ciebien's Rocky Mountain Motorcycle Holidays, then borrowed the same bike for a photo shoot with Canadian Biker's Jewel Black.

Which Sprint?

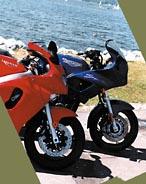

They ought

to be completely different, based on the fact that probably the only common

components are some engine internals - and they are. The most immediate

difference is how much lighter the new Sprint is, a fact made apparent while

manoeuvreing them for the camera. With its high centre of gravity, the '96

literally sways from side to side as the fuel in a full tank of gas sloshes

around. On the road, the high C. of G. means a tendency to fall in to corners,

as many victims of parking lot spills will testify.

Not so the ST. It

feels nimble and compact, like a 250 on steroids. It's dead steady at walking

pace, but at speed it turns more deliberately than the older machine, though

more predictably. Riding positions are

completely different. The '96

sits higher, with bars more conservatively raised and angled. The ST feels

cramped (to Jewel and me, anyway), with high footpegs, and the foot controls

well tucked in. On the road, the ST feels torquier with mucho pull from below

2,000 rpm. No doubt the weight saving is a factor here, with the extra 10

horses feeling like rather more. The characteristic patch of grating vibration

is still felt around 2,500 rpm, though the shrill whine from the straight-cut

primary gears has been modulated to a chirping whistle on the overrun.

completely different. The '96

sits higher, with bars more conservatively raised and angled. The ST feels

cramped (to Jewel and me, anyway), with high footpegs, and the foot controls

well tucked in. On the road, the ST feels torquier with mucho pull from below

2,000 rpm. No doubt the weight saving is a factor here, with the extra 10

horses feeling like rather more. The characteristic patch of grating vibration

is still felt around 2,500 rpm, though the shrill whine from the straight-cut

primary gears has been modulated to a chirping whistle on the overrun.

Forks are a great improvement with much less dive, in spite of what feels like more braking power. Again, the lower weight may be a factor. Instruments have been improved on the ST, now with a gas gauge as well as the warning light, and a digital odometer. But the idiot lights are still impossible to see in sunlight. It's a small thing, but God, as they say, is in the details. On both bikes the fairings provide much more protection than their scant looks suggest. A sudden squall on Hwy One a few weeks back on the '96 drenched my upper body and gloves, while most of the rest stayed dry. Similarly, climbing out of Nakusp with RMMH on the ST, a rainstorm soaked my hands, arms and chest but little else. The real innovation is the ST's ducted fairing, which cuts buffeting without reducing its effectiveness. The screen is cut much lower on the ST, however, though taller aftermarket screens are available.

A couple of other factors worthy of consideration, given the "sport touring" tag attached to both bikes. The ST's optional hardbags slot on to rails running under the tailpiece on either side, while the muffler rotates to a lower mounting position to allow room for the bags to fit. The result is a compact stowage system of limited capacity, although an optional matching 45-litre top box can also be fitted - for a price. Think in terms of a couple of G's for the lot. Less if bought with the bike. Foreswearing Triumph's luggage prices, I opted for pair of used 36 litre Givi hardbags and a wingrack kit for my '96, with a deluxe 50 litre topbox. Pets and small children now present no problem. But where the ST can save big is in fuel consumption. I've never bettered 6.3 litres per 100km (45mpg) on the '96, while the ST achieved a consistent 4.3 (65 mpg) on the RMMH tour. At that rate it would take about 170,000 km to save enough for a set of luggage...

And the verdict

is...

And the verdict

is...

To borrow the

old movie motto; the names are the same - only the stories have been

changed...Comparing these bikes is kind of unfair: one a 10-year-old, overbuilt

design given longevity by its fundamental rightness and durability; the other,

a product of Triumph's new-found ability to play in the big boys' sandbox -

fuel injection, magnesium castings and all. That said, I have a soft spot for

the quick steering and willing, if softer, engine of the '96.

They're both competent mile-eaters, but the modern sophistication of the ST - seamless, gushing power and outstanding rideability in an uncannily compact package - gives it a clear nod. And while I thought the ST's riding position would be a problem over distance, it proved surprisingly comfortable, like an old sweatshirt. So would I shell out the extra readies for the ST? More cash for more cachet? There's still lots of miles left in my '96, so the answer is - not yet. But when the times comes, the ST will likely top my shopping list.

(Thanks to Rocky Mountain Motorcycle Holidays for the loan of the Sprint ST. They're at (604) 938-0126 or www.rockymtnmoto.com)