Motorcyclist

January 2000

"Super Sleeper"

Article by Roland Brown

Article online with permission of Motorcyclist Magazine - Copyright 1999 Petersen Publishing Company, L.L.C.

Unauthorized reproduction or duplication prohibited.

Turbo Connection turns a stately Sprint ST into a truly psycho sport-tourer.

One moment there you are, sitting comfortably upright at the controls of your stately British Sport-tourer, your personal effects stowed safely in the Sprint ST's color-matched saddlebags - and suddenly, as you wind the throttle in second gear, the world explodes crazily into action. Like Prince Chrles instantly turned Charles Manson, your aristocratic Brit-bike leaps viciously into the air as 158 demented polo ponies break free of the barn…..

Welcome to Turbo Connection’s Triumph Sprint ST, arguably the world’s nastiest, most-inoffensive-looking, two-wheeled wolf in sheep’s clothing. If not for its boost gauge and discreet Turbo stickers on its fairing and bags, little would differentiate it from any other example of Hinckley’s finest all-’rounder. Yet the cunningly concealed, American-made turbo kit transforms the triple from sensible sport-tourer to rampaging hooligan. A supersleeper if there ever was one.

The standard Sprint ST ain’t slow, mind you, but this thing’s out there: 158.2 rear-wheel horsepower out there. That’s not just an increase of more than 50 percent vs. the standard bike’s 99.5 horsepower, measured on the same Dynojet dyno, it’s also slightly more than Suzuki’s Hayabusa typically makes. Given that the ‘Busa can reach an honest 190 mph, there’s the suggestion that with correct gearing this sober-suited British gent is likely good for well over 180 mph—even wearing saddlebags laden with cucumber sandwiches and flasks of Earl Grey.

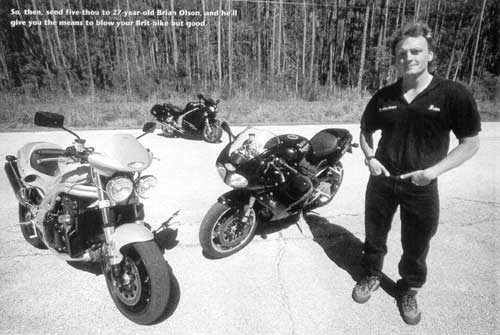

The guy responsible (if that’s the word) for this bike comes from aptly named Rapid City, South Dakota. Brian Olson is a 27-year-old bike freak, engineer, and computer buff who cut his teeth turbocharging cars in the late ‘80s, moved on to 200-plus horsepower blown snowmobiles, and then, after building a turbo Triumph of his own, set up a business last year under the name Turbo Connection to sell kits exclusively for the British triples.

Why Triumph? He has plenty of reasons. “I just like them", Olson says. “They’re something new, something different, yet they still have a heritage.” More practically, he adds: “Having three cylinders and fuel injection makes adding a turbo a lot easier. You don’t have to worry about the carb jetting; with these fuel-injected triples it seems they always run perfectly:’

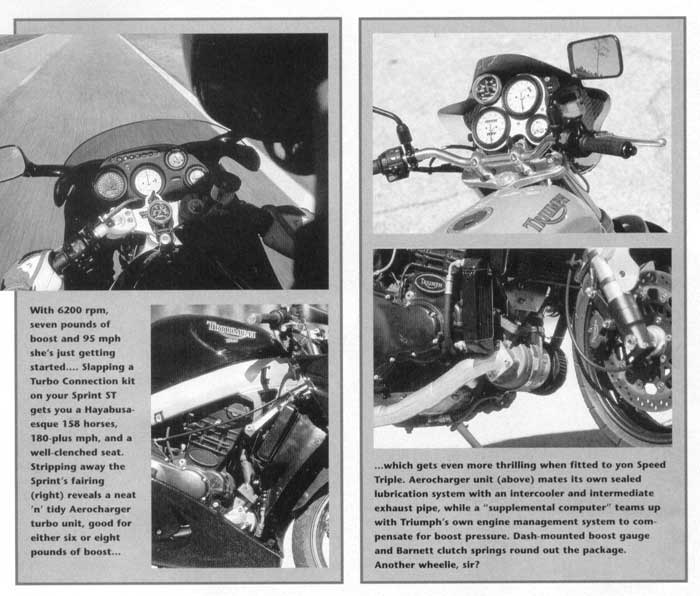

Olson’s $4999 kit is based around the compact Aerocharger turbo unit that, in recent years, has been successfully fitted to bikes ranging from Harleys to Honda CBR1100XXs. It’s a variable-vane turbo, meaning that maximum boost level is controlled not by a wastegate but by changing the position of the vanes. To increase boost you close them up; to reduce it you back them off to allow some exhaust gas to escape directly down the exhaust pipe.

“One great thing about the Aerocharger is that it has hardly any lag:’ Olson says. ‘And the three-cylinder engine helps too. With a four you get the number one and number four cylinders trying to counteract each other, so you don’t get such a clean pulse. With a triple the firing order is cleaner. They really spool up quick.”

The kit includes the turbo (which has its own sealed lubrication system), a purpose-made airbox, intermediate exhaust pipe (standard cans are used), an intercooler, boost gauge, slightly stiffer-than-stock Barnett clutch springs, and a supplemental computer, which works with the engine management system to compensate for boost pressure. Reduced compression ratio is not necessary, Olson says, so the cylinder head does not have to come off. He says an average owner can fit the kit in approximately one day.

Boost can be set to either six or eight psi. Pump gas is fine at the lower setting, which lifts peak output to 142 horsepower. Olson says the higher eight psi/155 bhp setting is also OK with super-unleaded fuel, provided you use max performance in small doses. “If you’re going to stretch it out for a long time you’d need an octane booster, but the motor is basically very strong. I’m working on a Stage II kit that will give 180 bhp. but that will require more mods.”

Great fun, no doubt, but a big feature of the Sprint’s turbo is that it’s so unobtrusive, both visually and when I rode the bike at a gentle pace. The blown motor idles smoothly, offers good low-rev response, and the only thing that really gives away the turbo’s existence, apart from stickers and boost gauge, is the slight rumbling noise from the unit itself. Even clutch action seems barely stiffer than stock as I head off for a thrash on some usefully long, straight and deserted roads around Daytona Beach.

Right off I know there’s something funny going on the moment I give the throttle a good tweak. The standard Sprint has plenty of midrange, but this bike is something else as the boost gauge needle snaps straight to the eight psi mark (why bother with the lower setting?), the revs head for the redline in third, and the bars get light as the Trumpet takes off for the distant horizon like a...well, pretty much like a slightly lighter, sit-up-and-beg Hayabusa.

Even from as low as three grand in top gear, throttle response is virtually instantaneous, and the acceleration brutal enough that seconds later the Sprint is still pulling hard while indicating 160 mph and well into the red at 10,000 rpm. With taller gearing it’d surely be good for more than 180 mph, yet the Triumph’s low-speed manners remain plenty civil.

The same is true of the similarly equipped (and identically powerful) Speed Triple, which backs up its he-man looks with suitably hairy-chested performance. Like the Sprint, the Speed Triple runs standard gearing, but this time the indicated 160 mph is slightly more interesting as my death grip on the bars sets the stockchassised (polished wheels apart) Triumph into a gentle wobble.

The ‘Triple backs up its straight-line muscle with some interesting sounds, too, as the cymbal-clash of the turbo, every time I shut the throttle to upshift, is much more audible without a fairing. Again, the motor runs very smoothly at low revs, though the naked bike’s stiffer clutch action is more obvious. Not that I’m complaining, given this bike kicks out the 100 bhp max of a standard Speed Triple at just 5500 rpm, four grand earlier than the normal 9500 rpm peak, and keeps piling on the power after that.

All of which helps explain the majestic, totally addictive way the Triumph lifts its front wheel when it is wound open in second gear. Never mind the normal trick of sitting back and pulling on the bar; the front wheel just keeps slowly and controllably lifting and lifting on a pure wave of power, in a way no standard production bike can manage.

To get that sort of performance boost out of a standard-looking Triumph triple is pretty special. The fact that it’s combined with such good manners (and apparent reliability, though it’s too soon to be sure) means that, for Triumph owners looking for serious speed, the Turbo Connection kit is a quick and certain path to sleeperdom.

Turbo Connection, 2019 Eclipse Ave., Rapid City, SD 57703; (605) 393-0816; e-mail Turbo595@aol com.