CB FEATURES

By Robert Smith

Tom Grenon

photos

With a full English breakfast,

including the infamous "black pudding" (don't ask...) floating in my stomach,

I found the Triumph Sprint RS where I'd left it - in a motorcycle parking

bay (Yes, they really exist!) just off Sloane Square in London's Chelsea district.

I climbed on to the firm seat, pulled in the clutch and - remembering not

to open the throttle - pushed the start button. The whine from the fuel pump

gave way to the familiar diesel tractor sound of the idling triple. The cable

clutch was noticeably heavier than the hydraulic type on my '96 Sprint, and

the gearbox notchier as I crunched into first. Pulling away, there was no

need to rev the engine - the steam engine torque kicked in as low as 1,500

rpm

With a full English breakfast,

including the infamous "black pudding" (don't ask...) floating in my stomach,

I found the Triumph Sprint RS where I'd left it - in a motorcycle parking

bay (Yes, they really exist!) just off Sloane Square in London's Chelsea district.

I climbed on to the firm seat, pulled in the clutch and - remembering not

to open the throttle - pushed the start button. The whine from the fuel pump

gave way to the familiar diesel tractor sound of the idling triple. The cable

clutch was noticeably heavier than the hydraulic type on my '96 Sprint, and

the gearbox notchier as I crunched into first. Pulling away, there was no

need to rev the engine - the steam engine torque kicked in as low as 1,500

rpm

The Sprint makes a pretty

good commuter tool in the Big Smoke. It has enough presence to intimidate

the scads of scooters that swarm around you at every intersection, yet it's

light and slender enough to squeeze between lines of cars. The torquey engine

is helpful, pulling you out of danger even when you forget to change down.

But I was disappointed not to be able to get into neutral easily at a standstill.

Other testers have not reported this to be a problem, so it  may have been my bike. I deked and

floated through London's gridlocked streets, enjoying the privilege of lane

splitting, to join the A1 Motorway. Sprinting north toward Peterborough and

Grantham, I was enjoying the Sprint's riding position - not as radical as

I'd expected and nicely balanced with the wind support from a 90 mph forward

speed - when an equation from high school physics popped into my brain....F=ma...

may have been my bike. I deked and

floated through London's gridlocked streets, enjoying the privilege of lane

splitting, to join the A1 Motorway. Sprinting north toward Peterborough and

Grantham, I was enjoying the Sprint's riding position - not as radical as

I'd expected and nicely balanced with the wind support from a 90 mph forward

speed - when an equation from high school physics popped into my brain....F=ma...

A simple expression of Newton's second law, I realized these three letters summed up my thoughts about the RS. I'd been struggling for a way to describe its superficial yet distinct differences from the Sprint ST. But where did that equation come from? Was it a subconscious channeling of the repeated road signs to Grantham, where Isaac Newton went to school? Hmmm... Let's see. The RS and ST share the same engine, so they apply the same force (F). But the RS weighs about eight kg less than the ST, so its mass (M) is about five per cent less. Even though this idea will be familiar to rocket scientists, it shouldn't take one to work out that if the force is the same and the mass smaller, acceleration will be greater. Like, duh!

So is the RS five per cent faster off the line? I didn't time them, but the RS definitely seems to haul its Bridgestone-clad ass away a decent amount quicker than the ST. And it isn't just straight-line acceleration. The weight peeled away from the T695 results in faster handling too. Throwing the bike from a quick left turn to a fast right reveals just how flickable the package has become. Less inertia means less effort to change direction. F=ma in action again.

Sweet-torquing

Sweet-torquing

Much has

been written in the motorcycle press about Triumph's 110-hp 955i triple and

its flat torque curve. Reviewers also talk a lot about torque rather than

power when it comes to today's chromo-cruisers. A flat torque curve apparently

makes for smooth power delivery - but why? With nothing much else to think

about as the signposts on the A1M slid by, I thought I'd see if I could

remember any more high school physics. Power is really just a measure of how

fast an engine can deliver torque. If an engine's torque curve is "flat" from,

say, 3,000 rpm to 6,000 rpm, the power output at 6,000 rpm will be twice that

at 3,000 rpm.

Motorcycles have a much higher power-to-weight ratio than your average car, yet don't necessarily turn in a much greater top speed. The reason? Wind resistance rather than weight is a much bigger factor in motorcycle top speed. Once you've got both of them rolling at a specific speed, the rolling resistance of a car and a bike aren't that much different. But a bike (and rider) usually has a higher drag factor, and usually has lower absolute power. So a motorcycle needs to build power as the revs climb to overcome drag, while a car engine needs more power (and torque) lower down to get the greater mass rolling.

So why is low-down torque

becoming a cruisebike's benchmark? Two things. One of  these is fashion, a subject of

which I have no understanding (ask my wife), and the other - well, like, why

change gear when you don't have to? I'd have to admit that the ability of

the RS to pull cleanly and strongly from 1,500 rpm is seductive, and makes

for some interesting acceleration tests - like crawl speed to over 160 kmh

in third gear. The real beauty of the RS/ST/Speed Triple engine is its faultless

delivery right up to the 9,500 rpm rev limiter.

these is fashion, a subject of

which I have no understanding (ask my wife), and the other - well, like, why

change gear when you don't have to? I'd have to admit that the ability of

the RS to pull cleanly and strongly from 1,500 rpm is seductive, and makes

for some interesting acceleration tests - like crawl speed to over 160 kmh

in third gear. The real beauty of the RS/ST/Speed Triple engine is its faultless

delivery right up to the 9,500 rpm rev limiter.

I've recently ridden a bunch of V-Twins in various configurations and

not found one that could match the triple at both ends of the spectrum. Either

the uneven power pulses made low rev  work tedious, or they buzzed mercilessly at higher revs - or both,

in the case of one high-profile European exotic. Similarly, a lauded cruiser

I rode would neither rev nor pull from low revs without sounding like a cement

mixer full of bowling balls. Three cylinders make for a pleasant sounding

and reasonably smooth motorcycle engine. Power pulses are an even 240 degrees

of revolution apart, and inherent vibration is much less than any twin configuration.

Yet the engine is compact enough to work well in a motorcycle chassis.

work tedious, or they buzzed mercilessly at higher revs - or both,

in the case of one high-profile European exotic. Similarly, a lauded cruiser

I rode would neither rev nor pull from low revs without sounding like a cement

mixer full of bowling balls. Three cylinders make for a pleasant sounding

and reasonably smooth motorcycle engine. Power pulses are an even 240 degrees

of revolution apart, and inherent vibration is much less than any twin configuration.

Yet the engine is compact enough to work well in a motorcycle chassis.

But that's all book

larnin'...

So much for theory. How

does the Sprint RS work out in practice? Remember when there was only one type

of motorcycle? What we now call a standard or retro? It had to do everything

from hauling a sidecar to road racing. Now you need a different kind of bike

for every day of the week, and two for Sundays.

If you follow motorcycle advertising, compromise is not a fashionable philosophy. But inevitably every modern motorcycle is a compromise of performance, ergonomics and price. The bike we choose just happens to suit our individual transient definition of "not compromising." In trying to define a new niche somewhere between sportbike and sport tourer, Triumph has succeeded with a brilliant trade-off. As a back-lane scratcher, the RS is fast enough and light enough, with a confidence-building plantedness that seems to defy centrifugal forces. As a sometime tourer, it's comfortable enough for 800 km days and well-mannered enough not to scare the horses. As a bar hopper, it's got great street cred, courtesy of eye-grabbing graphics. As a commuter, it's an agreeable taxi with a wild side. It'll do just about any job you want of a motorcycle - even haul a sidehack, one suspects - with a degree of...compromise. But most of all, it's just plain fun. No compromise there.

According to the words, the suspension

is taller and stiffer with shorter trail for quicker turning. Weight is trimmed

courtesy of the swingarm (now two-sided), instruments (a very compact electronic

display), bodywork etc. I expected the stiffer springs and lower weight to

cause some liveliness on rough surfaces, but no. Neither did the bicycle wander

nor get blown about on open windy roads - it always felt very stable. It's

definitely quicker to turn than the ST - it reminded me of a Buell in that

department. Riding position is compact and well tucked-in, while the narrow

bodywork cheats the wind rather than beating it. The compromises show up in

a few places. There's no gas gauge or hazard flashers, and the digital clock

rotates its display with the two trip counters - one only at a time. Forks

are adjustable for preload only. The higher-level exhaust makes for pillion

footpegs that would have your passenger's knees up around their ears (no sniggering

at the back...) and leaves little room for luggage. Then again, it's not a

tourer.

According to the words, the suspension

is taller and stiffer with shorter trail for quicker turning. Weight is trimmed

courtesy of the swingarm (now two-sided), instruments (a very compact electronic

display), bodywork etc. I expected the stiffer springs and lower weight to

cause some liveliness on rough surfaces, but no. Neither did the bicycle wander

nor get blown about on open windy roads - it always felt very stable. It's

definitely quicker to turn than the ST - it reminded me of a Buell in that

department. Riding position is compact and well tucked-in, while the narrow

bodywork cheats the wind rather than beating it. The compromises show up in

a few places. There's no gas gauge or hazard flashers, and the digital clock

rotates its display with the two trip counters - one only at a time. Forks

are adjustable for preload only. The higher-level exhaust makes for pillion

footpegs that would have your passenger's knees up around their ears (no sniggering

at the back...) and leaves little room for luggage. Then again, it's not a

tourer.

Neither does it have sportbike

redline screamability or bar-ends-on-the-deck leanability. Again, that's not

the point. But for fast cross-country work on Britain's winding A-roads while

mixing it with heavy traffic, the effortless top-gear passing and handy margin

of safety on braking and handling make it a very forgiving - and fast - package.

I enjoyed the RS best on the A47  between Peterborough and Leicester.

It's a fast, twisty two-lane blacktop favoured by cross-country truckers.

That means limited overtaking opportunities and quick decisions. The Sprint's

torque allowed me to pass the trucks quickly and safely without wasting valuable

seconds changing down. The assertive brakes allowed me to recover from a mistimed

pass. And the taut handling kept me secure through adverse-camber bends as

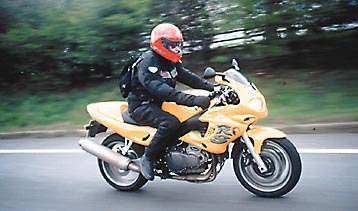

trucks thundered by inches away. Hinckley arrived too soon, and the yellow

peril handed back to its owners.

between Peterborough and Leicester.

It's a fast, twisty two-lane blacktop favoured by cross-country truckers.

That means limited overtaking opportunities and quick decisions. The Sprint's

torque allowed me to pass the trucks quickly and safely without wasting valuable

seconds changing down. The assertive brakes allowed me to recover from a mistimed

pass. And the taut handling kept me secure through adverse-camber bends as

trucks thundered by inches away. Hinckley arrived too soon, and the yellow

peril handed back to its owners.

What we have here, if anything, is a return to the standard bike concept of yore. A basic machine that will perform most road-going duties, but with the emphasis on performance and panache. Easier to define by what it isn't, rather than by what it is. But unless your level of non-compromise is Sadam Hussein-like, the RS would probably meet your needs.

This is a fast, fun package that would satisfy any sportbike enthusiast except those for whom only a race-rep rev-rocket will do. And if you want more creature comforts, there's always the ST...

Checkout Canadian Bikers website at http://canadianbiker.com